A Khanikhola & Dhikure Nepali Dashain

🏝 🏝 🏝 (3 Palm Trees)

I spoke on the family floor of their pink one-bedroom Kathmandu apartment as they listened closely while Shreya, the 15-year-old daughter, translated every word.

"When I learned Chinese, the world became noisy."

Her English was flawless, for I felt deep down that her translation was spot on.

“You see,” I said, “I learned people were just talking about the price of milk behind me on the elevator; they weren’t talking to me.”

However selfish that sounds, I explained that what I now heard was useless information. Whereas before, I lived in a world of silence that I was content with. Once I learned Chinese, what was once gibberish became something I could no longer tune out. For over two years of learning a language, I had put all this hope into what that nonsense meant, and then I found its true meaning: Milk.

Let's be clear, this is not an essay on why I've been content with having Chinese be my only second language and using it as an excuse for how I haven't bothered with Nepali as much as I should have; but in some honesty, I guess I like not to know what is said. Living in a world where you understand only what is spoken to you has its advantages.

However, this is the conversation we started the eighth day of Dashain out with, one where I was genuine and deep down a bit embarrassed that I couldn't connect with my housekeeper's family the way I wanted. They had asked me why my Nepali wasn't as good as my Chinese, and I came up with my most honest answer. The most important thing I said was that I had finally accepted their offer that I had declined for nearly five years, saying yes to Dashain dinner at their house and then two days of travel to the villages of both her and her husband.

Dashain is like the Nepali version of Christmas and Chinese New Year. Christmas because it's about family, Chinese New Year because it's so long, fifteen days to be exact. It's known as a time when family members get together on the tenth day to give one another tikas, a red dot that is a mixture of rice, yoghurt and powdered red vermilion. The colour symbolises the blood that ties the family together. The tika is a bright crimson preparation that you dab on a younger relative's forehead to bless their well-being for the upcoming year. It stains your forehead for days, and this time has turned my glasses red.

Sandhya insists I'm family and that it was more than usual that I should get tika with her relatives. I obliged and sat on her family room floor two nights before 'tika day', learning about the upcoming adventure while eating goat.

Yes, goat. 🐐

She told me we would start at seven in the morning, travel one hour to Khanikhola to visit her Mother and brother, and then travel two hours onward to Dhikure to see her husband Arjun's Mother. Dhikure, she warned me, was not your average place and was hardly a village. We would have to travel the last part on foot for the roads there couldn't take a car. She thought I was fragile, and I urged her I was not and could do with some off-roading. I soon discovered that the little car we brought was like the little engine that could. The fact I survived those roads is a miracle; the vehicle surviving them is an even larger one.

Khanikhola is what I would discover as an industrial hill station outside Kathmandu that hasn't had a census done since 1991. Thirty-one years ago, it had a population of 3127 people living in 512 individual households. Today I would say it has grown threefold but is still just a tiny village on the side of a mountain highway that gets a lot of traffic on the road to the capital city.

We stopped and met Sandhyas mother, both gentile and energetic.

She gave me a tika and a bowl of yoghurt for breakfast and then a tour of her small three-room country house overlooking a field of unripened cauliflower as if it were a mansion.

We took a family selfie, and her smile never faded.

She was proud.

The road to Dhikure was trying, and I learned that the name is a region, and the village I went to had no representation on the map.

Here is a road journey that ends with a red dirt path full of mango and papaya trees on the top of a hill that overlooks a valley.

It took about an hour to hike, and I was soaked with sweat when Arjun's family members greeted me with a tika and marigold necklace.

Arjun's Mother was the opposite of Sandhya's;

she was stoic and majestic.

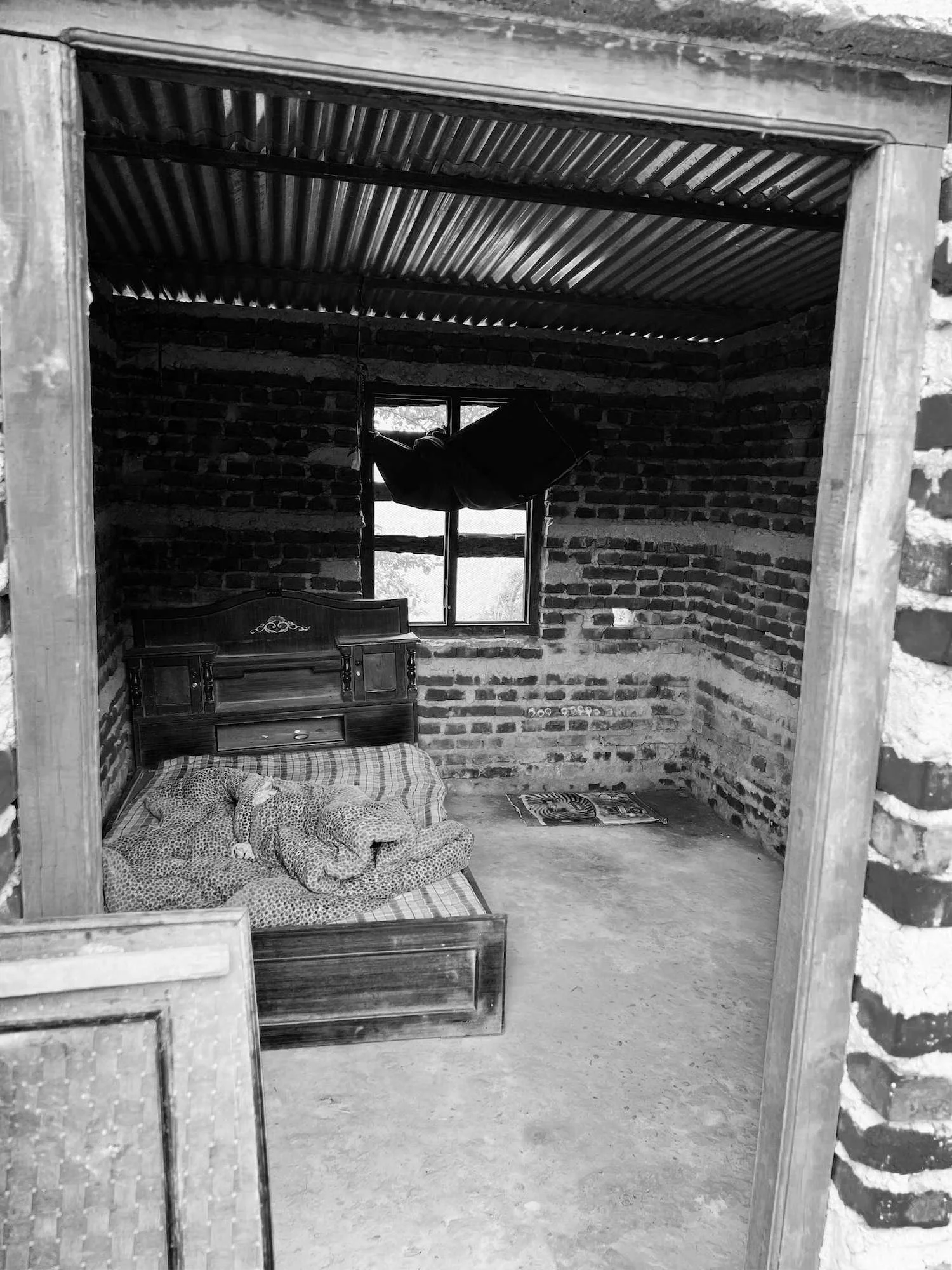

That night the villagers put me in what seemed to be the local guesthouse.

If it weren't dengue season, I wouldn't have minded, but reports of it were everywhere, and I would be lying if I wasn't a little bit anxious.

We then prepared

for a feast of freshly killed goat 🐐

and locally made raksi:

vodka on steroids.

It rained, and I stressed about getting home; being stuck in this village for days concerned me. The hospitality was grand, and the raksi was smooth as water, but it came with a hangover that I would soon learn would wrap itself around me for days.

That night's conversation was a blur, but I believe it was all about Arjun's family. To me, the villagers wished they lived closer and hoped that Arjun would carry them out of poverty, moving the Mother to the capital to live with them. However, in the end, everyone agreed they were all poor. That their situations were relative, that poverty is poverty. The Mother cried, and there was a quietness in the candlelit room. I sat there knowing I had the power to do something, that only a hundred dollars would make a difference, but I knew it was not my place. That I already was paying school fees and giving a salary. There is, I believe, an end to charity on one end, even though I wanted to give more. No one looked at me that night, wanting something. I think they knew that I also struggled and was doing the best I could, and I think that's what they saw in each other. Each person was doing their best.

“But to be honest, the four-hour-long conversation could have been about anything; it could have been about milk.”

I awoke to two mosquito bites and the thought of dengue. Rain was still coming down, and the image of every risky part of our journey loomed over me like a shadow of a doubt that I might not get home that day or the next. The trip back would be one where I would need to close my eyes and pray. But first, tika.

It was the tenth day of Dashain, and the Mother prepared for me a beautiful tika, and I got to give one to Sandhya'a husband and kids, for I was older.

At the time of tika, the elders also give "Dakshina", or a small amount of money, to younger relatives along with their blessings. I always felt guilty for accepting this money; I knew it was a lot to them. Now was my time to pay it back. So I stuck thousand rupee notes in each of their hands and blessed Shreya and her brother for a year of sound studies and Arjun for a year of wealth but, most notably, a safe drive back to Kathmandu.

My rating system:

-

An Oasis! Not only was the place incredible, but it’s on my list of places to live next.

-

I’ll definitely return because one time is not enough. Hidden treasures abound!

-

Been there, done that! Loved it, but I’ve crossed it off my list, and it’s time to move on.

-

This place is a shit hole! Might be interesting to some, but it was boring as hell to me.

-

Whatever you do, please don’t go here! It’s worse than the smell of an overflowing ashtray.

I give this adventure 🏝 🏝 🏝 (3 Palm Trees). Been there, done that! Loved it, but I’ve crossed it off my list, and it’s time to move on.